‘Collective management of copyright and related rights is justified where individual licensing is impossible or highly impracticable. In such a case, owners of rights trust collective management organizations (authors’ societies, performers’ unions, professional associations of producers, etc.) with exercising their rights on their behalf. The collective management organization monitors and authorizes uses, collects remuneration and distributes it among the owners of rights to whom it is due. This determines the basic structure of licensing in the field of collective management organizations.’

The above is an excerpt from the ‘WIPO National Seminar on Copyright, Related Rights, and collective management’ held in Khartoum, Sudan, in February 2005.

The report delves into the functions and optimal operations of Collective Management Organizations (CMOs), drawing a parallel between their role as that of agents who act on behalf of their members, with the members assuming the position of principals.

The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works which primarily focuses on establishing minimum standards for copyright protection and the rights of authors does not specifically address the workings of Collective Management Organizations (CMOs); it, however, indirectly recognizes the importance of collective management in copyright administration.

The Convention acknowledges the right of authors to authorize collective management of their rights through CMOs. It emphasizes the significance of collective management organizations in facilitating efficient licensing, royalty collection, and distribution of copyright-related revenues. It further encourages member countries to ensure that CMOs operate in a transparent and accountable manner, protecting the interests of rights holders while facilitating legitimate use of copyrighted works.

THE CASE FOR KENYA

In the Kenyan context, however, a contradictory narrative has emerged over the years.

Despite the legal obligation for Collective Management Organizations (CMOs) to act in the best interests of rights holders, the reality reveals ongoing conflicts and struggles between CMOS and rights holders i.e. artists.

And this brings us to the focus of today’s article.

*****

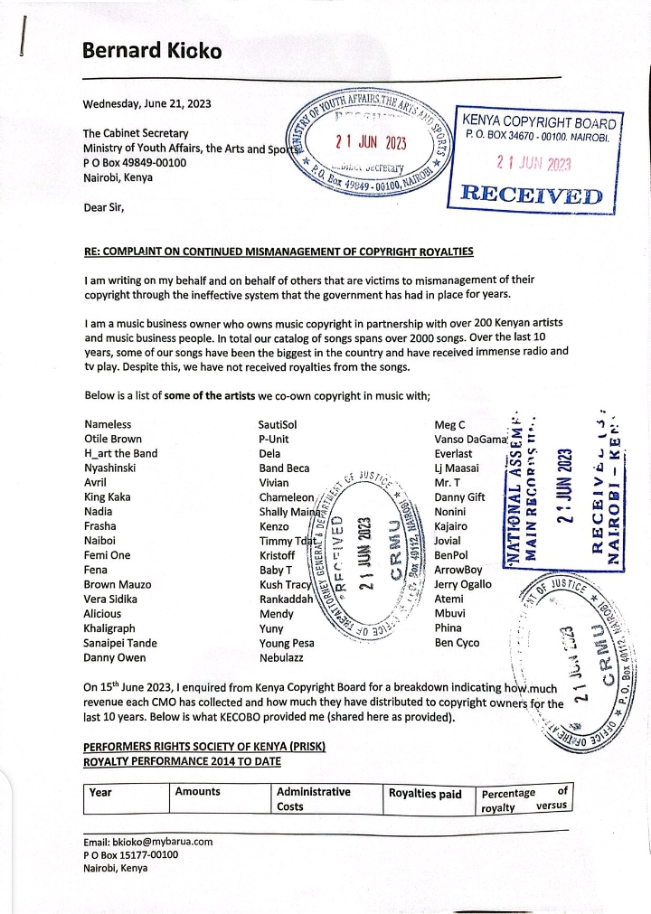

Today’s focus shall concentrate on a letter written by one Mr. Bernard Kioko to the Cabinet Secretary for the Ministry of Youth Affairs, the Arts and Sports, demanding accountability for the mismanagement of his royalties from CMOs operational within the music industry in Kenya i.e. PRISK (Performers Rights Society of Kenya), KAMP (Kenya Association of Music Producer) and MCSK (Music Copyright Society)

Bernard’s letter reads in part:

“I am a music business owner who owns music copyright in partnership with over 200 Kenyan artists and music business people. In total, our catalog of songs spans over 2000 songs. Over the last 10 years, some of our songs have been the biggest in the country and have received immense radio and tv play. Despite this, we have not received royalties from the songs”

His letter then goes on to state that upon his inquiry to KECOBO for royalties statements for royalties collected by CMOs between the years 2014 to 2021, that he managed to procure a breakdown of royalties collected; a breakdown that paints a grim reality for the future of distribution of music royalties in Kenya as shown below.

The letter concludes with Mr. Bernard Kioko demanding accountability from the Ministry and seeking audience with the Cabinet Secretary towards finding solutions to the current state of affairs.

WHAT THE LAW SAYS

The term ‘Collective management organization’is defined in sum within Section 2 of the Copyright Act as an organization approved and authorized by the Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO) to negotiate for the collection and distribution of royalties on behalf of members. The Act further lists the criteria for which a body may be licensed to operate as a CMO or be deregistered from doing so.

Section 12 of the Copyright Collective Management Regulations 2020 then spells out the specific functions of CMO’s as follows:

- To act in the best interests of its members;

- Not to impose on its members any obligations which are not objectively necessary for the protection of the members’ rights and interests or for the effective management of the members’ rights; and,

- To act for the collective benefit of its members as its sole or main purpose and which fulfils one or both of the following criteria i.e. being owned or controlled by its members; and being organized on a not-for-profit basis.

Section 13 of the Regulations further obligate CMOs to ensure that:

- Their members have the right to authorize to the collective management of members’ rights; categories of rights; and types of works;

- (j) In the organization’s memorandum and articles of association, there is an express provision that the organization’s primary objective is the collection and distribution royalties on behalf of its members.

Looking through the lens of royalties collected over the past few years, the discrepancy within the royalty collection infrastructure in Kenya isn’t in the collecting of the said royalties, but in their distribution.

The royalty statements revealed in Mr. Kioko’s letter show that a chunk of money collected goes towards catering for what are termed ‘administrative costs’. Of course, what is defined as ‘administrative costs’ would beg one to review the CMOs Memoranda and Articles of Association that govern their running. (P.S if you have a copy, please send it to us via info@artlawkenya.com ).

Q. What then, are administrative costs?

‘Administrative costs’ typically refer to the expenses incurred by an organization in order to manage its day-to-day operations and support its overall functioning. These costs are typically associated with the administrative and managerial activities required to keep the organization running smoothly.

Administrative costs can include various expenses, such as:

- Salaries and benefits paid to administrative staff, executives, and management personnel who oversee and coordinate the organization’s operations.

- Office space and utilities i.e. costs associated with renting or owning office space, including rent or mortgage payments, utilities (such as electricity, water, and heating/cooling), maintenance, and insurance.

- Office supplies and equipment such as stationery, printer ink, and computer software and equipment (including computers, printers, telephones, and furniture).

- Communication and technology such as telephone, internet, and mobile phone plans and technology infrastructure (including hardware, software, servers, and data storage).

- Professional service fees paid for external professional services, such as legal and accounting services, consultancy, auditing, or IT support.

- Licensing and permits (if any e.g. county government business permits).

- Training and professional development.

- Travel and transportation.

- Miscellaneous expenses such as recruitment, marketing and advertising, office cleaning, and security services.

Proper management and control of administrative costs for ANY organization is however crucial for maintaining the financial health and efficiency of an organization and its stakeholders/members.

What, then, is the proper balance between these administrative expenses and ensuring fair equitable compensation for the actual members’ rights? And are these administrative expenses justified?

Perhaps it was time to put these CMOs to task in accordance with best corporate governance structures as well as employ the already existing mechanisms within the law, some of which include:

- The Constitution of Kenya 2010.

A petition can be filed well within its right under Article 11 (Promotion of Culture), Article 40 (Protection of Right to Property), Article 43 (Economic and Social Rights), and Article 47 (Right to Fair Administrative Action). Let us be reminded that protection of one’s property is a fundamental constitutional human right provided for within the Bill of Rights. In Sleek Lady Cosmetics Limited v County Executive, Transport, Infrastructure and Public Works, County Government of Mombasa & another [2020] eKLR, the High Court in appreciating this allowed Counsel’s prayer for conservatory orders based on the Petitioners right to artistic creativity; fair administrative action; the right to privacy; social economic and cultural rights; consumer protection rights; property right and that the aforementioned rights can only be limited in accordance to Article 24 of the Constitution.

- The Copyright Act

In my opinion (which is subject to correction), one of the main reasons for the repeated deregistration and re-registration of certain CMOs is the limitation imposed on registration based on specific classes of rights – Section 46(5). Members are negatively impacted by this limitation, placing the Board in a difficult position where they must either rely on the possibility of another CMO applying for a license within the same class of rights or, if no alternative arises, reluctantly grant licenses to the already existing CMOs.

I, however, I do not possess any information regarding the utilization of Section 46 (11) by the Board, which entails imposing sanctions on members of the Board of Directors or Management where deregistration could potentially impede the rights of members instead of assisting them.

Perhaps employing this as a deterrence may be worth a shot.

- The Copyright Collective Management Regulations

Encouragement of members to unite and demand accountability at the CMO’s Annual General Meetings in accordance with Section 15 of the Regulations.

The Companies Act 2015 provides for incorporated companies to hold what is called an ‘annual general meeting’ of the company’s members or stakeholders to discuss the running of the company. It is at this meeting that company management are interrogated over decisions made in the interests of the company. An AGM is key and all stakeholders or members are encouraged to attend.

The same applies to AGMs for CMOS.

Section 15 provides for CMOs to ensure that a general meeting of its members is convened at least once a year. It is at this same general meeting of members that members shall have the power to decide:

- on any amendments to the memorandum and articles of association of the organization, and the membership terms of the collective management organization;

- the appointment and dismissal of the organization’s officials, review the officials’ performance and approve their remuneration and other benefits;

- the policy on the distribution of amounts due to members and right holders;

- the policy on the use of non-distributable amounts;

- the investment policy on rights revenue and any income arising from the investment of rights revenue;

- the policy on deductions from rights revenue and any income arising from the investment of rights revenue;

- the risk management policy;

- the retained amounts and the purpose of the retention of the amounts

Section 18 further obliges prudence on the part of any person who manages the CMOs business to use prudent administrative procedures, accounting procedures and internal control mechanisms. Further, the board of a CMO shall seek the approval of distribution rules from the general meeting of its members.

If you ask me, there is nothing prudent about overspending royalties on administrative costs when the very presence of your mandate, stems from rights holders ability to keep generating the same copyrightable content capable of generating royalties that you benefit from.

This is to say that the power really is in the hands of the rights holder. Copyright being a private right means that it MUST be the rights holders to raise issue. The Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO) can only do so much.

- Principles of the law of Agency

The principles of the law of agency establish the legal relationship between an agent and a principal and dictate that:

- An agent owes several duties to the principal, including loyalty, obedience, reasonable care, and disclosure of relevant information.

- An agent can be held personally liable for any breach of their duties to the principal, such as acting outside the scope of their authority, failing to act in the principal’s best interests, or disclosing confidential information without authorization.

- A breach by the agent may occur if they fail to fulfill their obligations or act contrary to the principal’s instructions or interests. This breach can result in legal consequences, including potential claims for damages or termination of the agency relationship.

BEST BUSINESS PRACTICES AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE MEASURES

Going by best business practices and corporate governance structures that could influence the operations of CMOs, CMOs should:

- maintain transparent systems for tracking and reporting the usage of musical works by licensees.

- Represent, in earnest, the collective rights of a significant number of rights holders via protecting the interests of their members.

IN CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the mismanagement of music royalties in Kenya is a complex issue that requires a multi-faceted approach to address effectively. Here are some possible solutions that could help improve the situation:

- Implementation of robust auditing mechanisms to ensure proper collection and distribution of royalties to artists via establishing clear guidelines and regulations for the management of funds, and regularly monitoring the operations of collection societies to prevent mismanagement.

- Improved data management systems and the employment of better/new/simpler/cost-effective technologies to help streamline the collection and distribution of royalties, ensuring that artists are properly identified, registered, and compensated for their works.

- Education and awareness programs targeting both artists and music users, such as broadcasters, streaming platforms, and event organizers. Educate artists on their rights, the importance of registering their works, and how to monitor and track their royalties. Similarly, inform music users about their obligations to pay royalties and the consequences of non-compliance.

- Enforcement of legal action against non-compliant music users.

- Collaboration between key stakeholders, including artists, collection societies, government bodies, and music users as well as encouraged dialogue to develop effective strategies for fair royalty distribution and collection. Perhaps through engaging with international organizations and industry experts to learn from global best practices and adapt them to the Kenyan context i.e. de-monopolization of CMOs.

- Legislative reforms via reviewing and updating existing copyright laws and regulations to align with best practices.

It is important to note that for the best possible result, these solutions would be implemented in a coordinated manner, involving all relevant stakeholders, and with a long-term commitment to improving the music industry’s ecosystem in Kenya.

At the end of the day, in a case where owners of rights (authors’ societies, performers’ unions, professional associations of producers, etc.) cannot trust CMOs with exercising their rights on their behalf, then collective management of copyright and related rights isn’t justified.

It may just be time to get uncomfortable.

“The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again but expecting different results.”

– Albert Einstein

READER DISCLAIMER – This article in no way asserts an actionable legal opinion, but mere thoughts within the current environment within which I work in, both as an advocate and as a music composer.